Summary of “Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for refractory cardiac arrest”

Abstract Summary: Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR), using venoarterial ECMO during refractory cardiac arrest, can restore circulation and improve outcomes compared with conventional CPR (CCPR) alone. While evidence suggests ECPR enhances survival with favorable neurological recovery, its complexity, resource demands, costs, and complication risks restrict widespread use. The authors discuss the current evidence base, patient selection criteria, procedural considerations, and future research needs in ECPR.

ARREST=Advanced Reperfusion Strategies for Patients with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest and Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation. CPC=cerebral performance category. CPR=cardiopulmonary resuscitation. ECPR=extracorporeal CPR. ICU=intensive care unit. INCEPTION=Early Initiation of Extracorporeal Life Support in Refractory Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. OHCA=out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. RCT=randomised controlled trial. ROSC=return of spontaneous circulation. *Numbers are mean (SD). †Numbers are median (IQR).

Key Points:

- Definition and Scope: ECPR involves initiating venoarterial ECMO during ongoing CPR when conventional CPR fails to achieve sustained return of spontaneous circulation, providing temporary circulatory and oxygenation support.

- Current Evidence (OHCA): Three recent randomized trials (ARREST, Prague OHCA, INCEPTION) showed mixed outcomes, with significant survival benefits observed primarily in highly selected patients treated rapidly (<60 minutes post-collapse) in specialized centers.

- Current Evidence (IHCA): For in-hospital cardiac arrests (IHCA), observational studies consistently indicate reduced mortality with ECPR, but prospective randomized trial data remain lacking.

- Patient Selection Criteria: Optimal candidates (“PRO” criteria) typically include younger age (<65 years), witnessed arrest, immediate bystander CPR, shockable rhythms, short expected low-flow duration, and absence of severe comorbidities.

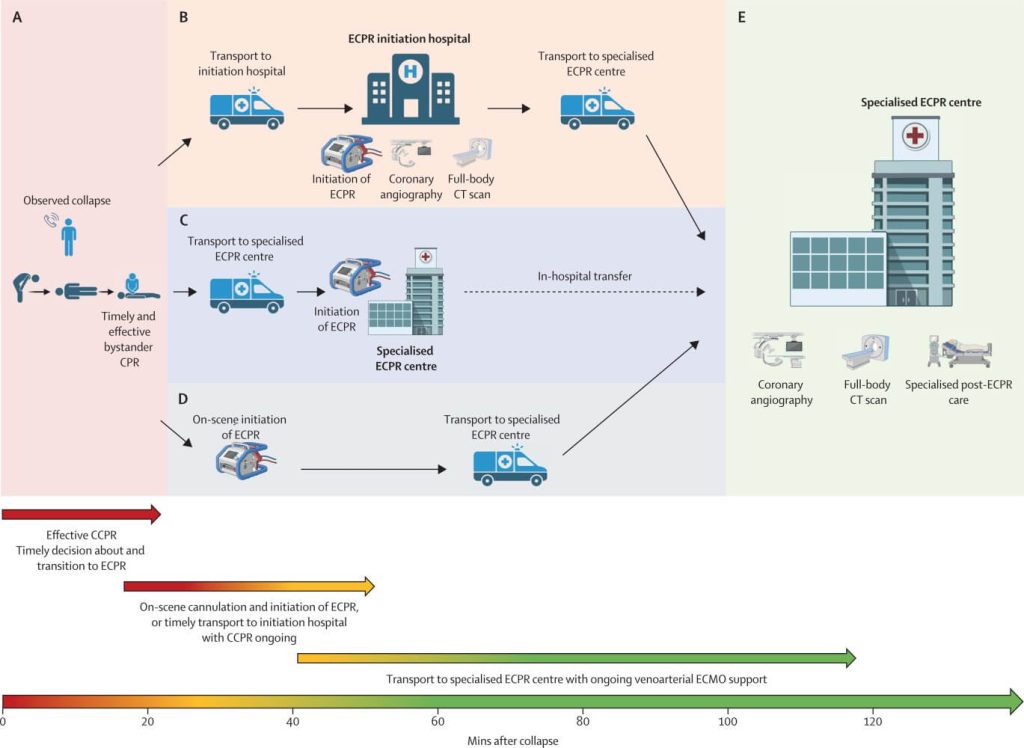

- Timing and Logistics: Rapid initiation (ideally within 60 minutes from collapse) is crucial. Early decision-making about ECPR eligibility significantly impacts outcomes, with shorter low-flow times strongly associated with better neurological survival.

- Cannulation Techniques: Percutaneous femoral access under ultrasound guidance is preferred due to lower complication rates, faster insertion (typically 10–15 minutes), and reduced risk of neurological and vascular injuries.

- Complications of ECPR: Major complications include limb ischemia (5–15%), significant bleeding events (9–40%), and intracranial hemorrhage (5–7%). Continuous monitoring (e.g., near-infrared spectroscopy) and routine distal perfusion cannulation can mitigate these risks.

- Post-ECPR Care Protocol: Effective management post-ECPR includes immediate coronary angiography, full-body CT scans, targeted temperature management (33–34°C), meticulous anticoagulation management, and vigilant monitoring for complications like LV distension.

- Long-term Outcomes: Survivors generally exhibit good neurological outcomes (CPC ≤2). Long-term data suggest favorable functional recovery and acceptable quality of life, with high proportions returning to independent living or employment.

- Economic and Ethical Considerations: High costs (average ~$75,000 per patient, ~$130,000 per survivor), intensive resource demands, and limited availability raise ethical concerns about equitable access. Cost-effectiveness remains uncertain and highly dependent on local health systems and implementation quality.

PRO criteria describe situations associated with a reasonable chance of neurologically favourable survival. CON criteria describe situations with major contributions to the risk of mortality or neurologically unfavourable survival. Therefore, indication for ECPR should be made very critically, and only in individual cases. STOP criteria reflect situations without a reasonable chance of meaningful survival. Therefore, ECPR should not be considered if any of these criteria are present.

Conclusion: ECPR, while promising, remains complex and resource-intensive. It shows substantial survival benefits in selected patients with refractory cardiac arrest managed in specialized, highly coordinated healthcare systems. Broader adoption requires rigorous patient selection, optimal timing, advanced training, and continued research to refine protocols and outcomes.

If cardiac arrest is considered refractory to CCPR, early decision for transition to ECPR should be made, and further steps should be initiated according to local system organisation aiming at establishment of ECPR (ie, circuit connected to the patient circulation and running) within 60 mins after cardiac arrest (B–D). (A) Timely recognition of cardiac arrest and effective bystander CPR, and timely decision about initiation of ECPR and activation of ECPR team. (B) Early transport with ongoing effective CCPR to initiation hospital for initiation of ECPR. With ongoing venoarterial ECMO support, depending on local conditions and availability, coronary angiography or full-body CT, or both, can be performed in initiation hospital before transport of the patient to the specialised ECPR centre for specialised post-ECPR ICU care. (C) Early transport with ongoing effective CCPR to specialised ECPR centre, if this is the nearest place for in-hospital ECPR initiation. (D) On-scene initiation of ECPR, with ongoing venoarterial ECMO support and transport of the patient to specialised ECPR centre. (E) With ongoing venoarterial ECMO support, coronary angiography (if indicated) or full-body CT, or both, should be performed before in-hospital transfer of the patient to specialised post-ECPR ICU care. CPR=cardiopulmonary resuscitation. CCPR=conventional CPR. ECPR=extracorporeal CPR. ICU=intensive-care unit.

Watch the following video on “EuroELSO Webinar – „ECPR in adults – an update“ by EuroELSO European Chapter of ELSO

Discussion Questions:

- How can healthcare systems address logistical and ethical challenges to ensure equitable access to ECPR?

- What are the barriers preventing broader implementation of high-fidelity simulation training for ECPR teams?

- In what ways can future clinical trials better establish definitive evidence regarding the optimal timing and selection criteria for ECPR?

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.