Sickle Cell Disease and Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Multidisciplinary Approach to High-Risk Cardiac Surgery

- Home

- Cannulation

- Current Page

1. Introduction

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a chronic, inherited blood disorder resulting from a single point mutation in the β-globin gene. This mutation leads to the production of hemoglobin S (HbS), which polymerizes under low oxygen conditions, causing red blood cells to assume a characteristic sickle shape. These sickled cells are rigid, prone to hemolysis, and can occlude small blood vessels, leading to ischemia and organ damage.

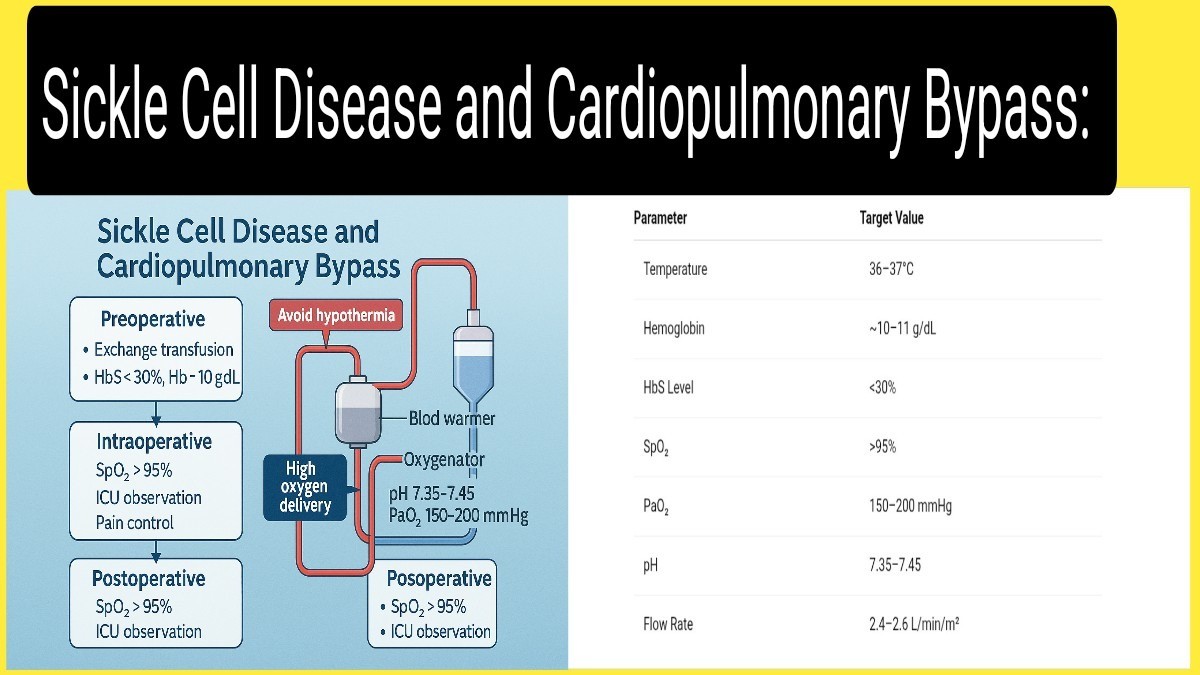

Cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) presents a unique challenge in patients with SCD. CPB introduces multiple stressors—hypoxia, hypothermia, acidosis, and inflammation—that may precipitate sickling crises, potentially resulting in severe morbidity or mortality. As such, managing a patient with SCD during CPB requires a carefully coordinated, multidisciplinary approach.

This article explores the pathophysiology of SCD, highlights specific risks during CPB, and outlines a comprehensive perioperative management strategy to mitigate complications.

2. Understanding Sickle Cell Disease in the Surgical Context

SCD is characterized by chronic hemolytic anemia, intermittent vaso-occlusive crises, and progressive end-organ damage. Under stress conditions such as low oxygen tension, low pH, and hypothermia—common during surgery—sickled erythrocytes become rigid and adhesive, obstructing capillaries and causing ischemia.

Patients with SCD may already have compromised cardiopulmonary function due to chronic anemia, pulmonary hypertension, or prior strokes, which further increases surgical risk. Therefore, a detailed preoperative assessment and proactive planning are essential.

Surgical triggers of sickling include:

- Hypoxia: Deoxygenated HbS polymerizes, increasing sickling.

- Hypothermia: Slows microcirculation and increases blood viscosity.

- Acidosis: Shifts the oxygen dissociation curve, reducing oxygen delivery.

- Hemodynamic stress: CPB-induced hemolysis increases free hemoglobin.

- Systemic inflammation: Increases endothelial adhesion and cytokine release.

3. Why Cardiopulmonary Bypass is High-Risk in SCD

Cardiopulmonary bypass can exacerbate the pathophysiological derangements of SCD. CPB circuits expose blood to non-physiologic surfaces, resulting in hemolysis and systemic inflammatory responses. Cooling techniques, while neuroprotective in the general population, can be dangerous for SCD patients.

Critical CPB-associated risks in SCD include:

- Hypothermia: Even mild cooling increases sickling potential. Normothermia is strongly recommended.

- Hemolysis: Mechanical shear forces damage fragile sickled RBCs.

- Acidosis and hypoxemia: Potentiate HbS polymerization.

- Complement activation: Exacerbates inflammatory responses and endothelial dysfunction.

- Capillary sludging and stasis: Worsens tissue perfusion and oxygenation.

4. Preoperative Optimization

Optimal outcomes begin with thorough preoperative planning, involving hematologists, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, and surgeons. The goal is to minimize the sickling risk before surgery begins.

4.1 Hematology Consultation

All SCD patients should undergo hematology evaluation weeks prior to surgery. Transfusion strategy and crisis history must be reviewed. Individualized plans are preferable.

4.2 Exchange Transfusion

Partial exchange transfusion is recommended to reduce HbS concentration to below 30% and raise hemoglobin to 10–11 g/dL. This significantly reduces sickling risk.

Reference: Vichinsky et al., NEJM, 1995

4.3 Infection Screening

Due to functional asplenia, SCD patients are at high risk for sepsis. Screen for occult infections and start prophylactic antibiotics preoperatively.

4.4 Hydration and Oxygenation

Maintain adequate hydration and ensure oxygen saturation consistently exceeds 95% with supplemental oxygen if needed. Avoid dehydration, which increases blood viscosity.

4.5 Baseline Testing and Imaging

- ECG and echocardiography: Assess cardiac function and pulmonary pressures.

- Chest X-ray: Look for signs of previous acute chest syndrome.

- Liver and renal panels: Evaluate baseline organ function.

- Transcranial Doppler: In patients with cerebrovascular history, to assess stroke risk.

5. Intraoperative Management: Normothermia and Beyond

Once the patient enters the operating room, meticulous attention to physiological stability becomes paramount. CPB protocols must be adjusted to preserve normothermia, optimal oxygen delivery, and acid–base balance.

5.1 Temperature Management

Avoid all forms of hypothermia. Maintain core temperature between 36–37°C throughout CPB. Use warming blankets, fluid warmers, and heat exchangers in the CPB circuit.

5.2 Perfusion Strategy

- Use high-flow CPB (2.4–2.6 L/min/m²) to maintain perfusion pressure

- Avoid low-flow states and minimize pump suction to reduce hemolysis.

- Consider leukocyte-depleting filters and biocompatible circuits to limit inflammation.

5.3 Acid–Base and Oxygen Monitoring

- Maintain PaO₂ between 150–200 mmHg.

- Keep arterial pH between 7.35–7.45.

- Monitor lactate levels to detect tissue hypoxia early.

- Regular ABGs and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) may aid in real-time assessment.

5.4 Anesthesia Considerations

- Ensure deep, stable anesthesia to avoid sympathetic surges.

- Use agents that do not depress respiratory drive excessively postoperatively.

- Avoid vasoconstrictors; consider vasodilatory agents if needed.

6. Postoperative Care and Monitoring

The early postoperative period is critical, particularly the first 72 hours, during which complications such as acute chest syndrome (ACS), stroke, or VOC are most likely to occur.

6.1 ICU Monitoring

Patients should be closely monitored in a high-dependency or intensive care setting with continuous pulse oximetry, cardiac telemetry, and regular ABGs. Monitor for signs of ACS, stroke, or renal dysfunction.

6.2 Pain Control

Use a multimodal analgesic approach including opioids, NSAIDs, and regional techniques where appropriate. Adequate pain control prevents VOC and reduces sympathetic stimulation.

6.3 Fluid Balance

Maintain strict input/output records. Avoid fluid overload which may contribute to pulmonary edema, and avoid dehydration which can exacerbate sickling.

6.4 Thromboprophylaxis

SCD patients have an elevated baseline risk of thromboembolic events. Prophylactic anticoagulation should be initiated postoperatively, unless contraindicated.

7. Case Studies and Clinical Evidence

Several case studies support the use of exchange transfusion and normothermia in improving CPB outcomes in SCD:

- Koshy et al. (1990) reported favorable outcomes with preoperative transfusion protocols and normothermic CPB.

- Fitzhugh et al. (2010) showed that careful intraoperative management including normothermia and oxygenation resulted in zero VOC events in their cohort.

These studies reinforce that tailored perioperative management significantly reduces complications.

8. Conclusion

Cardiac surgery in patients with Sickle Cell Disease poses serious but manageable risks. With early planning, individualized transfusion strategies, intraoperative normothermia, and vigilant postoperative care, the outcomes can be significantly improved.

Key strategies include:

- Preoperative HbS reduction to <30%

- Maintenance of normothermia during CPB

- Aggressive oxygenation and acid–base management

- Comprehensive ICU care and pain control

A multidisciplinary, protocol-driven approach is essential to ensure safety and optimize outcomes.

Asif Mushtaq: Chief Perfusionist at Punjab Institute of Cardiology, Lahore, with 27 years of experience. Passionate about ECMO, perfusion education, and advancing perfusion science internationally.