The Role of Cannula Design in Optimizing CPB Flow Dynamics

- Home

- Cannulation

- Current Page

In the complex world of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), where precision, safety, and efficiency govern every aspect of patient care, the significance of flow dynamics cannot be overstated. While the primary focus often gravitates toward pump technology, oxygenators, and perfusion protocols, an often underappreciated component quietly plays a pivotal role: the cannula.

Cannula design directly influences hemodynamic performance during CPB, impacting everything from circuit efficiency to end-organ perfusion. As the interface between the extracorporeal circuit and the patient’s vascular system, arterial and venous cannulas serve as both conduits and regulators of flow, making their design a critical determinant of clinical outcomes [1,2].

Why Flow Dynamics Matter in Cardiopulmonary Bypass

Cardiopulmonary bypass temporarily takes over the functions of the heart and lungs, maintaining circulation and oxygenation while the heart is arrested for surgery. The overarching goal of CPB is to provide adequate systemic perfusion while minimizing the physiological stress imposed by non-physiological circulation.

Flow dynamics — the pattern, velocity, and distribution of blood flow within the circuit and patient — are central to achieving this balance. Poor flow dynamics can result in several adverse effects, including:

- Non-uniform organ perfusion, increasing the risk of ischemia or hyperperfusion injury [3].

- Hemolysis, due to excessive shear forces damaging red blood cells [4].

- Microbubble formation and embolization, resulting from turbulence or cavitation [5].

- Activation of inflammatory pathways, secondary to non-laminar flow patterns [6].

Optimizing flow is not simply about achieving a target flow rate; it’s about ensuring stable, laminar, and controlled delivery of blood to the tissues. This is where cannula design becomes a central player.

Cannula Design: More Than Just a Tube

At first glance, a CPB cannula may seem like a simple hollow tube, but its engineering reflects a complex intersection of fluid mechanics, material science, and clinical requirements. Each design parameter — from diameter to tip configuration — directly affects how blood enters or exits the extracorporeal circuit.

Venous Cannulas

Venous cannulas are responsible for draining deoxygenated blood from the venous circulation into the bypass circuit. They must achieve high flow rates with minimal negative pressure to avoid:

- Venous collapse or «chatter»

- Air entrainment

- Shear-induced hemolysis

Key design considerations include:

- Diameter and length: Larger diameters reduce resistance and negative pressure but may be limited by vascular anatomy [7].

- Tip design: Straight, angled, or curved tips can aid in optimal positioning within the right atrium or superior/inferior vena cava.

- Multi-stage designs: These incorporate multiple drainage ports to improve venous return efficiency, particularly in bicaval or minimally invasive setups [8].

- Wire reinforcement: Prevents kinking while maintaining flexibility.

Arterial Cannulas

Arterial cannulas return oxygenated blood to the systemic circulation. Their design is critical to avoid:

- Jet streaming and recirculation zones, which can create local high-shear regions [9].

- Aortic wall trauma or dissection [10].

- Embolic phenomena due to disrupted laminar flow [11].

Key design features include:

- Tip dispersion designs: Diffuse the high-velocity jet to reduce shear stress on the aortic wall [12].

- Side holes: Allow partial flow dispersion but must be carefully balanced to avoid disturbing overall flow patterns.

- Tapered or beveled tips: Aid in smoother flow transitions.

- Material coatings: Heparin-bonded surfaces reduce thrombogenicity and inflammatory response [13].

Innovations in Cannula Technology

Cannula technology has evolved significantly over the past two decades. Modern designs reflect a better understanding of hemodynamic principles and technological advancements such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, which allow manufacturers to visualize and optimize flow patterns before clinical use.

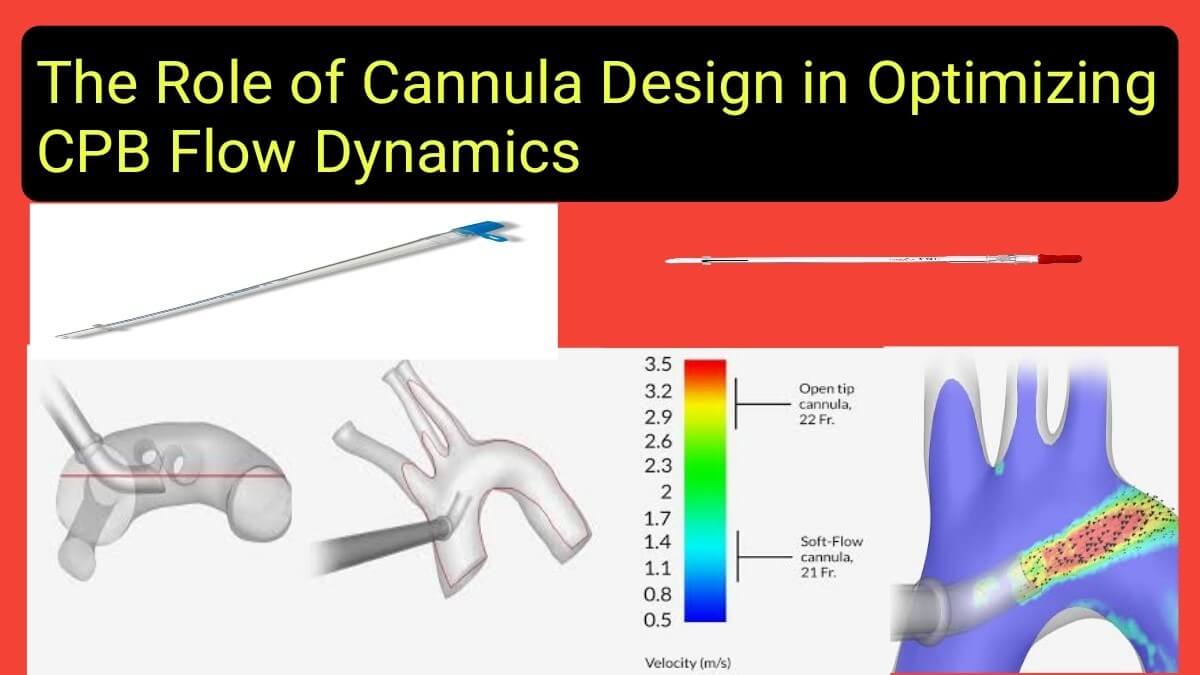

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in Cannula Design

CFD has become an essential tool for simulating how blood flows through cannulas under varying physiological conditions. This technology allows engineers to model:

- Velocity profiles

- Shear stress distributions

- Pressure gradients

- Turbulence and recirculation zones

By analyzing these factors, manufacturers can iteratively refine designs to minimize adverse flow conditions, reduce hemolysis, and improve overall perfusion efficiency [14].

Biocompatible Materials and Coatings

Beyond mechanical design, material composition has seen remarkable advancements. Modern cannulas often feature:

- Heparin-coated surfaces, reducing thrombus formation and inflammation [15].

- Polyurethane or silicone construction, providing biocompatibility and flexibility.

- Wire-reinforced walls, preventing collapse while maintaining pliability.

These materials enhance patient safety by minimizing the activation of coagulation and inflammatory cascades, ultimately reducing postoperative complications such as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [16].

Minimally Invasive and Specialized Designs

With the growth of minimally invasive and robotic cardiac surgery, specialized cannula designs have emerged to meet new clinical challenges:

- Long, flexible venous cannulas designed for peripheral access (e.g., femoral or jugular cannulation) [17].

- Low-profile arterial cannulas, enabling insertion through smaller incisions.

- Dual-lumen cannulas for veno-venous ECMO, optimizing drainage and reinfusion from a single site [18].

Clinical Implications of Cannula Selection

The importance of proper cannula selection extends beyond engineering into direct clinical outcomes. An inappropriate cannula choice can compromise the entire perfusion strategy, even if the rest of the circuit is functioning optimally.

Circuit Efficiency

- A well-designed cannula ensures stable venous return and arterial delivery with minimal circuit pressures [19].

- Reduces the likelihood of high negative pressures and venous collapse.

- Minimizes energy loss within the circuit.

Organ Protection

- Stable flow promotes uniform organ perfusion, lowering risks of neurological injury, acute kidney injury, and gastrointestinal ischemia [20].

- Reduces shear-induced blood trauma, preserving red blood cell integrity [21].

Patient Safety

- Optimal designs lower the risk of embolic events by minimizing turbulent flows [22].

- Reduce aortic wall injury, particularly in fragile patients or those with atherosclerotic disease [23].

Special Clinical Situations

- In minimally invasive surgery, long flexible cannulas allow for effective perfusion through limited access sites.

- In pediatric and neonatal cases, tiny vessel diameters demand specially engineered small-bore cannulas to maintain adequate flows without excessive shear [24].

- In aortic dissections, careful selection of arterial cannula placement and design can minimize the risk of extending dissection planes [25].

The Human Factor: Cannula Design Meets Perfusion Expertise

While advancements in cannula technology are critical, they cannot substitute for the clinical expertise of the perfusionist and surgical team. Understanding how different designs interact with unique patient anatomy and surgical goals remains a vital skill. For example:

- Positioning a multi-stage venous cannula requires knowledge of intracardiac anatomy to avoid preferential drainage or incomplete venous return.

- Selecting an arterial cannula in patients with ascending aortic disease demands careful attention to minimize localized shear forces.

Technology and human expertise must work hand in hand to fully optimize outcomes [26].

Conclusion: Small Details, Big Impact

In the high-stakes environment of cardiac surgery, success is often determined by the mastery of small but critical details. Cannula design — though sometimes overlooked — plays a fundamental role in shaping flow dynamics, protecting end-organs, and ensuring safe, effective CPB.

As technology continues to evolve, we will likely see further refinements driven by computational modeling, advanced biomaterials, and growing clinical experience. However, even the most advanced cannula is only as effective as the team that selects, positions, and manages it.

By paying close attention to cannula design and its impact on flow dynamics, we can continue to refine perfusion practice, reduce complications, and improve patient outcomes — one cannula at a time.

Asif Mushtaq: Chief Perfusionist at Punjab Institute of Cardiology, Lahore, with 27 years of experience. Passionate about ECMO, perfusion education, and advancing perfusion science internationally.